I grew up eating Hokkien mee a lot. It is still one of my favorite dishes to this day. For those who have no inkling of what Hokkien mee is, it is a dish of thick yellow noodles stir-fried in black soy sauce with pork lard, prawns and cabbage, and served with a must-have chilli shrimp paste condiment also known as sambal belacan in Malay.

Contrary to what people believe, this popular dish did not originate from the Fujian province of China but was allegedly created by Wong Kian Lee, an immigrant of Hokkien descent who ran a hawker stall in the area now known as Kampung Baru in Kuala Lumpur, in the 1920s.

Many Malaysian Chinese are of Hokkien descent with a vast majority of them residing in the states of Penang, Selangor and Johor. Besides Hokkien, there are many other dialect groups such as Hakka, Cantonese, Teochew, Hainanese, et cetera whose forefathers – many of whom originated from south China – made this country their home many centuries ago.

There is no specific rule in the Chinese custom that prohibits intermarriage among the various dialect groups. Hence, interdialect group marriages among the Chinese were commonly practiced in those days and even more so in this modern day and time.

What it means to be ‘Hakkien’

Whenever someone asked me which dialect group do I belong to, I simply say, “I am “Hakkien” – one who is born Hakka but could only speak Hokkien.

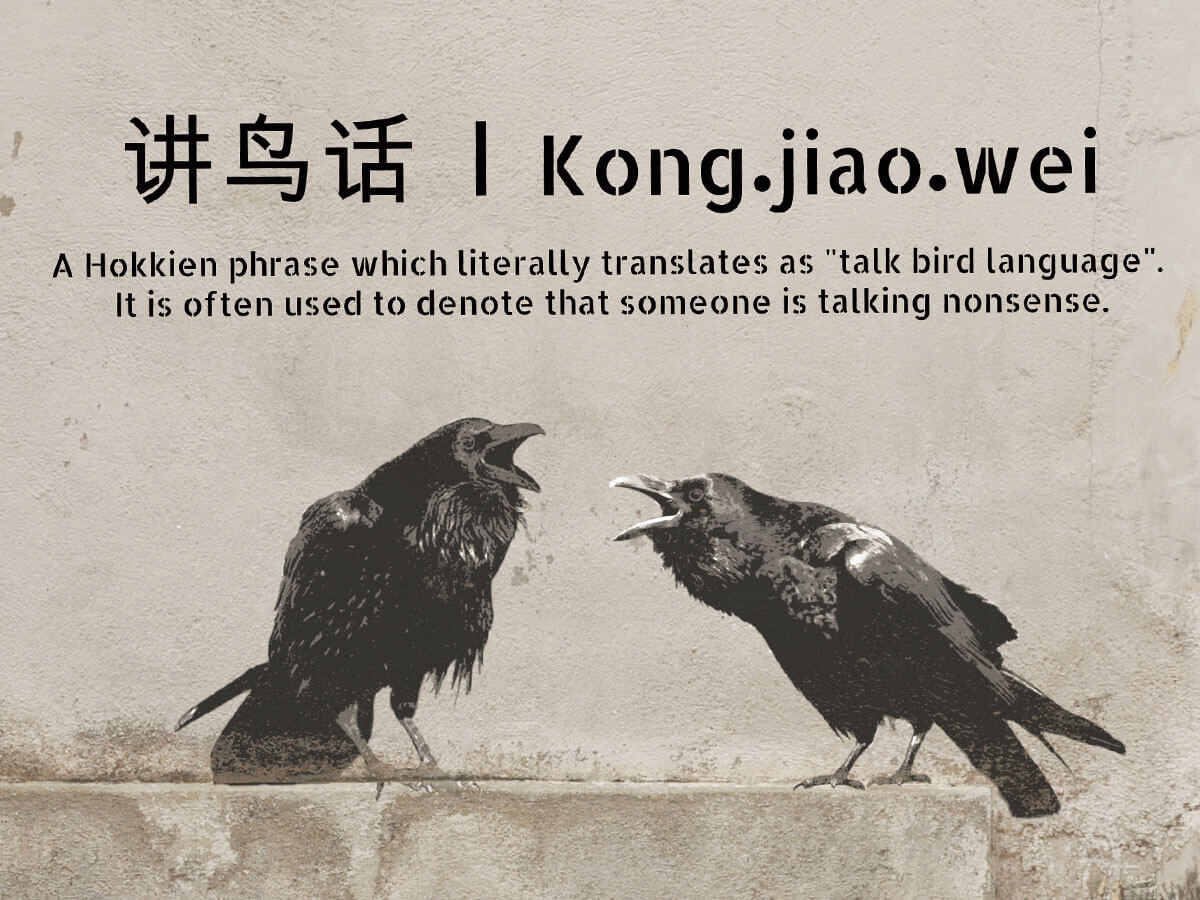

No, I am not “speaking bird language” here. My father is Hakka and my late mother was Hokkien. I was born and raised in Klang, and lived there until the late 1990s before moving to a new township which is just an hour’s drive away.

Klang was – and still is, I believe – a Hokkien-majority town. One would only need to look at the huge mansion-like building that houses the Klang Hokkien Association and be convinced. There are no other Chinese guild buildings around town that could come close to surpassing its sheer size and grandeur.

Many non-Hokkien Klangites like me grew up speaking Hokkien as our mother tongue. I guess this custom was quite prevalent in many towns and villages back then, as Chinese of different dialect groups tended to use the dominant Chinese dialect of the locality for social interactions and communication between dialect groups.

Hokkien was once widely spoken in the community and played a significant role in defining Klang’s place-identity, but today its usage is not as prevalent as it was in the past.

While Hokkien is still largely spoken among the elderly folks or street-market traders, those of the younger generation appear to be lacking in enthusiasm to use Hokkien as a lingua franca in their daily inter-communal communication; partly because some see Hokkien usage as an indicative of a lack of education, vulgarity and backwardness. The further decline of usage is also attributed to the rise of Mandarin as the preferred language among the Chinese-educated families.

Many studies conducted by linguistic scholars in Penang and Singapore have revealed that the use of non-Mandarin dialects in their respective regions is in dire decline and this phenomenon is in tandem with the decline of many other minority languages in the world. According to a study by a United Nations independent expert, Rita Izsák, “half of the world’s estimated 6,000-plus languages will likely die out by the end of the century” if no effort is made to preserve them.

The waning of place-identity

I am no linguist expert nor am I a dialect proponent, but my concern is less with the decline of dialects per se than with the waning of place-identity. What I am particularly interested in is the relation between language and place, and am curious as to how one would articulate that relationship.

That is, what role does language play in making places? Can language be a tool that helps us to uncover and discover the authenticity of places and its people?

Take Hokkien, for example. There are two versions of Hokkien spoken in this region today. From Penang in the north to Johor in the south, each state has developed a sort of their own unique localized variant of Hokkien, the difference in which can be easily distinguished by the sound of the speaker’s voice and words he or she uses.

Generally, all versions of Hokkien are mainly derived from the Quanzhou and Zhangzhou variants – the two oldest dialects of Southern Min spoken in Fujian province. The Hokkien of the southern states of Malaysia speak the Quanzhou variant, while the version used in the northern states is derived from the Zhangzhou variant, and is commonly known as “Penang Hokkien”.

Interestingly, the northern version of Hokkien contains more Malay loanwords than the Hokkien spoken in the southern states. As such, it is said that a Hokkien speaker from the south would find it much easier to speak Hokkien to Taiwanese or Hokkien speakers from Fujian province, rather than one from the north.

Such is the potency of place to shape language as it evolves. Conversely, language has the power to shape how places are perceived and interpreted, as each language may paint a different picture of a place to the people who speak the language.

Great places are not only topographic entities, they are also socially constructed by “voices” of people in interaction with one another to form ideas that would then translate into action, and the action would in turn culminate in making. As Yi Fu-Tuan, a well-known geographer, once wrote: “It is not possible to understand or to explain the physical motions that produce place without overhearing […] the speech – the exchange of words – that lies behind them.”

A personal creative endeavour

Speech and spoken words have always held a certain appeal to me, particularly when they are used to ascribe and associate meaning to a place, or to bring back memories of a distant past that are closely linked to one’s birthplace.

My work-related visits to my hometown Klang, of late, has brought back many memories of my younger days, growing up in a town where Hokkien is the only dialect I could understand or speak with competence.

Hence what started as a recollection of my early years quickly grew into an impetus for personal creative endeavour. And thus my first foray into public art began. My hope is that my artwork could assume the role of an interlocutor to stimulate thinking, to prompt dialogue, and to heighten our awareness of our communal roots and values.

For many foodies, Klang may be a town synonymous for its authentic bak kut teh, but for me, Klang is more than just a town where I was born. It is also a town infused with meaning and relevance that holds the key to my past. I am not simply a Chinese Malaysian; I am a “Hakkien” whose substantial identity is very much rooted in the habitus of Hokkien-ness.

Ti.Tu – Hokkien for spider. Catching spiders to fight is probably unheard of by many urban kids nowadays but it was one of the many childhood pastimes that I had, especially after- school hours.

Kong,Jiao.Wei – A Hokkien phrase which literally translates as talk bird language. It is often used to denote someone is talking nonsense.

Kay.poh – A Hokkien phrase for busybody or someone who is nosy.

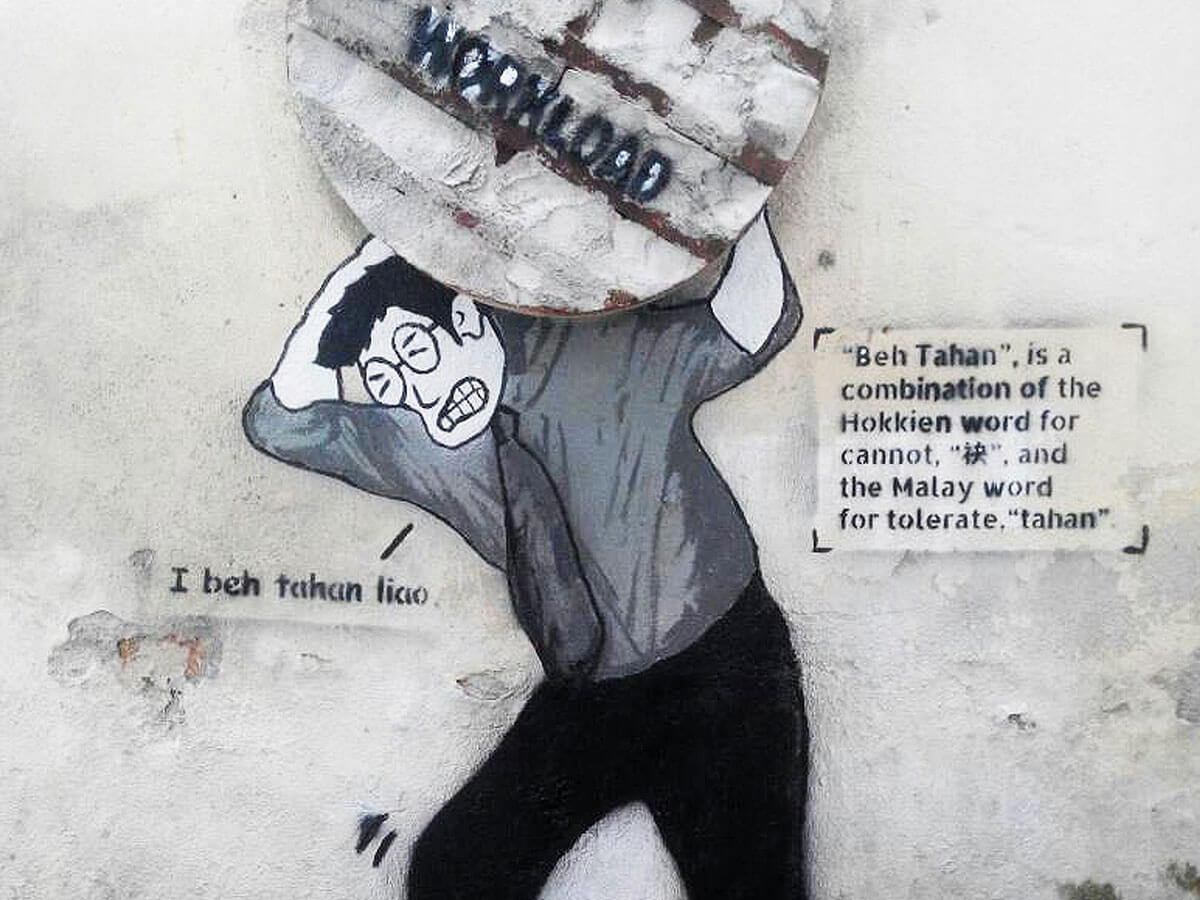

Beh Tahan – A combination of the Hokkien word for cannot, andthe Malay word for tolerate, tahan.

The artworks shown here can be found in the vicinity of Jalan Stesyen 1, Klang. This self-initiated public art project would not have been possible without local community support, particularly from the Klang City Rejuvenation team.

Website: Klang City Rejuvenation Project

Facebook: We Love Klang