The dilemma of a reunion

Produced by KiniTV

To be continued…

Produced by KiniTV

To be continued…

It seems that every time we log onto Facebook, we’re presented with new petitions to sign. “Save the Whales!”, “Ban computer games!”, “Support our charity!” – all these and more vie for our attention and signatures both physical and electronic.

While the majority of them will probably be ignored or deleted from your screen, some of them may interest you enough to read and sign. But does signing a petition actually do anything apart from giving you warm fuzzy feelings and the satisfaction of doing something good?

Let’s take a look at some of the popular petitions in the past…

Malaysia Wants Coldplay Petition (2016)

Did it work?

Maybe.

While Coldplay still has no plans to stop by Malaysia, They have, however, increased another show in Singapore due to “overwhelming demand”, giving regional fans more chances to enjoy their music.

Petition to stop Malaysia’s barbaric method of getting rid of strays (2014)

Did it make a difference?

Yes.

In 2015, Malaysia passed the Animal Welfare Act which has stricter punishments for animal abusers. The new act imposes a minimum of RM20, 000 and possible jail time to convicted offenders, a hundred times more expensive compared to the previously used Animal Act of 1953. Many activists saw the new legislation as a step forward, though they were still concerned about the fact that mandatory sterilization of pets was not added to the act.

No to Parking Fee Increase and Abolishment of Maximum Parking Charge (2010)

In 2010, the management of Mid Valley Megamall decided to increase their parking rates by almost 200% and remove the maximum rate of RM 6. This drew complaints and criticism from many tenants who felt that the increase was unjustified. A petition was started which eventually managed to gather 402 signatures.

Did it change their minds?

No.

The management at Mid Valley decided to keep their new parking rates. Drivers are charged either RM 2 (weekday) or RM 3 (weekend) for the first 3 hours and an additional RM 1 for each subsequent hour. There is no maximum rate, so the longer you stay the higher your fee becomes. The new parking rate remains to this day.

You see, a petition by itself isn’t going to change anything. Even if a million people sign a petition saying that robbing a bank should be legal, the cops will still arrest you if you and your friends try to rob a bank.

A petition has four main purposes:

So handing in a petition to the authorities is simply telling them “Hey, all these people don’t like this situation. You need to do something about it.”

The rise of online petitions have caused an increase in “slactivists”.

“Slactivist” is a word used to describe people who claim to support a certain cause but are unwilling to actually put any effort into championing it. They’ll click likes and sign petitions, but aren’t willing to go out to protest or take part in active events.

Part of the reason for this is simply the fact that people have their own lives to lead. Most people are too busy working and earning money to spend a lot of time or energy on activism. Even if they’re concerned about something, only the most dedicated people are willing to take time off to go and protest for something that might not even affect them directly.

Online petitions allow more people to get involved, giving them a chance to express their views without forcing them to change their lifestyles in order to campaign.

Petitions give the common citizens a platform to be heard. It allows them to send a message to those in power, letting them know if they’re doing something that will negatively affect a lot of people.

But do they have to listen?

In the UK, the government has a system in place to deal with petitions, including the website http://petition.parliament.uk/. If a petition collects 10,000 signatures, they will receive a response from the government. If a petition collects 100,000 signatures, it will be debated in parliament unless the issue has already been debated recently or is planned to be debated in the near future.

The USA has something similar: http://petitions.whitehouse.gov/ is a website that allows people to make petitions online and “speak directly to the Administration”.

At the moment, Malaysia does not have anything like this. Petitions in Malaysia are handed over to the government official closest to the issue, who then gets to decide what to do with it. No matter how many signatures a petition receives, it is not guaranteed a response. If the receiver simply decides to ignore your petition, there’s not much you can do about it.

Because petitions are simply the first step.

There’s a reason why social campaigns are known as “movements”. Like a car, they require energy to move forward. A petition is like a spark, a reaction to an event or circumstance that the public finds unacceptable.

A successful petition serves as a peaceful outlet for the people’s anger while drawing them together to fight for a cause greater than themselves. It brings the issue to the forefront, raising awareness and informing the receiver about how strongly the public feels about the issue.

While petitions fail to gain the momentum they need to succeed, there is a growing body of literature showing how effective it can be. In particular, organizations or individuals who are accountable to public opinion are more willing to listen to petitions since bad publicity can have such a strong negative effect on them.

Large petitions can also have unintentional side effects – drawing attention from the international community, inspiring signers to take further action or even incentivising other organizations to change their behavior.

Here are some of the on-going petitions we found. To sign or not to sign. That is the question.

Agree or Disagree? Share.

Undoubtedly, Bollywood movie ‘Dangal’ has been one of the hottest movies among Malaysian moviegoers since it hit the screens at the end of 2016.

This should come as no surprise. The movie stars Indian award-winning actor Aamir Khan and features a compelling and uncommon plot about professional wrestling.

Spoiler alert!

Based on a true story, the biographical sports drama follows the journey of a former national wrestling champion Mahavir Singh Phogat (played by Khan) as he trains his two daughters to become gold and silver medalists at the 2010 Commonwealth Games.

The film has garnered much praise for promoting gender equality, especially in patriarchal India where it is still illegal to determine the sex of a child before birth due to widespread female infanticide.

But whether or not it truly challenges patriarchy is a matter for debate.

The film opens with Mahavir expressing

That is until his eldest daughters Geeta and Babita, enraged after being teased by the village boys, decided to wallop the boys. It was a lightbulb moment for Mahavir – why crave for a son when his daughters can be trained just the same to achieve gold for India?

Girls to men

To achieve his dream, he disregarded objections by his wife and the gossip among his

The scenes of the girls training directly confront gender stereotypes in rural India.

For example, when Mahavir’s wife frets over how her husband is ruining the girls’ chances of attracting a suitor, he tells her that when the girls are champions, it is they who will pick their partners and not the other way around.

When she tells him it is unheard of for girls to be wrestling, he asks: “So you think our girls are not as good as boys?”

Most obvious was the juxtaposition between the Phogat girls and their friend, a teen bride.

Upset that his daughters missed practice for something as frivolous as a wedding party, Mahavir stormed the party and struck Geeta across the face.

Crying to their friend, Geeta and Babita lament that their father is no father at all, forcing them to give up things that matter to them – their free time, their childhood, their long hair – to wrestle against boys in the mud.

But in the pivotal scene, their friend the teen bride tells them they are wrong. Unlike Mahavir, she said, her parents see her as nothing but a burden to be passed on to a groom for a price. Mahavir, she said, was giving his daughters a life.

Two dads little different

Even so, one cannot help but note that both the teen bride’s father and Mahavir are holding on to the same rope of patriarchy.

Mahavir, who had the final say on everything, forced his daughters to bend to his will of winning a gold medal for the country. This was not much different from forcing his daughter to get married. The only difference is that Mahavir’s motive was much more acceptable in the perspective of modern society.

The scene with the teen bride marked a change in the Phogat girls who buy into their father’s dream, catapulting the film many years forward to when a young adult Geeta becomes

Now a national athlete, Geeta has to leave her father’s tutelage to train at a national sports institution far from home.

Here, Mahavir’s power as “father” is challenged by a greater power – the “state” – represented by the sports institution and the national coach, who immediately undermines Mahavir’s techniques in front of his daughter.

The move to the national sports institution also allowed Geeta to expand her wings beyond sports. If before she was tightly regimented, in this bright new world she starts growing her hair, painting her fingernails, goes shopping and watches movies with her friends.

Slowly, she decides to abandon the so-called “weak skills” that she learned from Mahavir and adapted to what was offered by her coach.

And this ultimately turns to a confrontation between Geeta and Mahavir. In a visit to her hometown, Geeta defeats the now middle-aged Mahavir in a wrestling match.

The treatment of Geeta henceforth is that of a “rebel”, and her rebellion against the patriarchal force of her father was duly

In back to

It is only after Geeta makes amends with her father and returns to her role as “obedient daughter” that she breaks her losing spell.

A poignant scene between Mahavir and Geeta, where he advises her to be a role model for all girls in India, may again persuade the audience of the feminist streak in the film. But alas, the denouement brings us back to the question of overarching patriarchy.

As much as the film strongly challenges stereotypes and gender roles in Indian society, ultimately,

After Geeta wins the gold medal in a

In the pinnacle scene, she shows her father the medal, and he for the first time in her life, says: “Syabas.”

If you were watching this, what did you see? Did you see a father who secured a bright future for his daughter, or did you see a daughter who fulfilled her father’s long-awaited dream?

Was Dangal really promoting gender equality and challenging the traditional values of the Indian society, or did it merely show a new form of gender oppression under the guise of national glory?

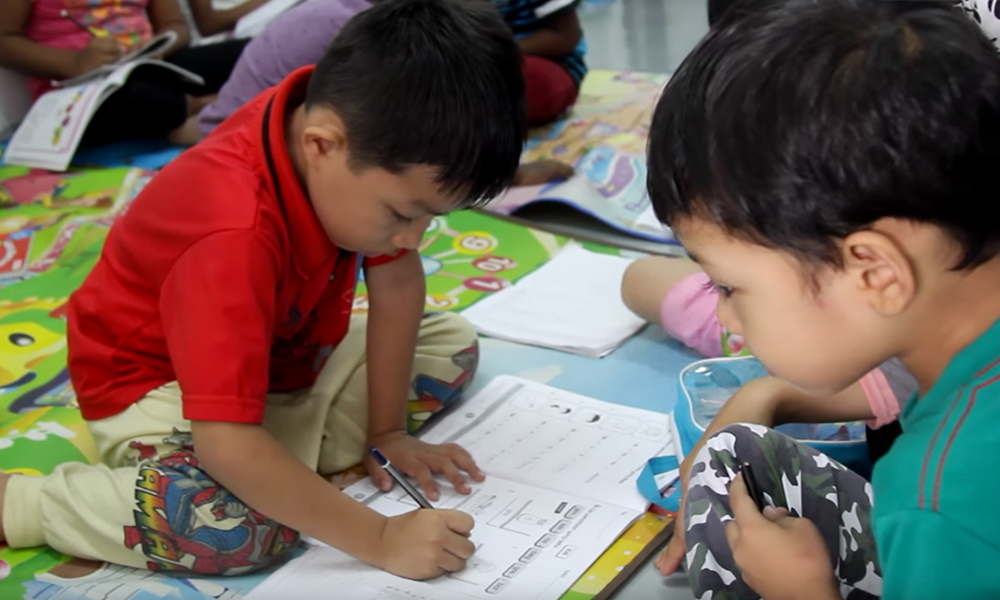

Desa Mentari Satu is one of many places in the country filled with poor blue collar workers and their families. With few funds and little resources to aid them, many of them still struggle to make ends meet. The people who live in places like this tend to go about unseen and unheard from the authorities, making them extremely vulnerable to crime and abuse.

James Nayagam, the founder and chairman of The Suriana Welfare Society, has spent over 35 years working to help children from impoverished families. The NGO runs several free art and music classes, providing the children with a place where they can play and express themselves freely. The group also carefully observes their student’s behaviours in order to identify if they are victims of abuse.

“ We ask them to relate to us what happens in their house. And then during play therapy we see how they play with the children. During art therapy we see what colors they use. If they say they feel sad, we ask ‘who made you sad?’ and then the story will come out. ”

The Suriana Welfare Society is one of the only organisations in Malaysia that works to identify and prevent child abuse among the lower sections of society. Unfortunately, there are only so many that they can help. While the statistics are kept locked up by the Official Secrets Act (OSA), many believe that a majority of child abuse cases go unreported. According to the police, over 13, 000 child sex abuse cases were reported in Malaysia between 2012 and 2016, of which only 1% resulted in convictions.

The horrible thing is that is may only be the tip of the iceberg – it is believed that many other cases go unreported due to fear or apathy.

“ We used to teach the child. But the children say they don’t want to tell the adult because they’ll say ‘what nonsense are you talking about? ”

Shaney Cheng, the Training and Education Executive of P.S the Children.

The arrest of paedophile Richard Huckle in 2016 revealed a shockingly large number of victims that had apparently slipped through the system. The shock and outrage caused by this revelation prompted Prime Minister Najib Razak to set up a special task force to “look into ways to combat sexual crimes against children” But for many victims, it was already too late.

Child abuse is a horrible crime, one that can leave permanent scars. The physical and mental negative effects can potentially ruin the victim’s life. The problems are only amplified by an apathetic, judgemental society that is quick to complain and blurt out their outrage on social media, only to forget all about the problem in a few days. Some conservative families even try to force their children to marry their rapists in order to save face!

Richard Huckle the pedophile

To fight back against this menace, we as Malaysians must stop trying to ignore the problem or pretending that it doesn’t exist. Child abuse is a stain on the fabric of society, one that should be removed as thoroughly as possible.

To find out more about what you can do to identify or prevent child abuse, contact Suriana Welfare Society at their facebook

Or visit their official website

Video by P.S. the Children

Child Trafficking is a serious problem in Malaysia

Underaged boys and girls are sold or abducted from all neighbouring countries into Malaysia for prostitution and child labour.

Children forced to engage in sexual acts for money

Burmese children are smuggled into Malaysia for begging

Children work up to 17 hours a day in rubber plantations

Children used in recycling garbage dumps in urban areas

A country can be involved in Child Trafficking in 3 ways

Where the children come from

Where the children are moved through or kept temporarily

Where the children will finally end up

Malaysia is one of the few countries that is counted to be all three.

Traffickers take advantage of children imported from less developed countries such as Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Eastern Europe, Russia, Uzbekistan, India as well as those from impoverished local families.

While some traffickers keep the children here, others use Malaysia as a stopping point before sending their ‘products’ to places as far away as Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, Europe, Canada, USA, Australia, and South America.

> 1,000,000

More than 1 million children are being brought into the sex market ever year worldwide.

That’s 2 innocent children forced into prostitution every minute.

“Did you ask to have sex with all these men?”

“Did you ask to be sold as a sex slave?”

“Nursery Crimes” by P.S. the Children

What does the Law say?

Currently, those who are caught dealing with child trafficking or prostitution in Malaysia are charged under the Child Act, a series of laws meant to provide protection for children in need.

Although the Child Act was amended recently, the punishment for sexually abusing a child is simply a fine of RM50,000 and/or no more than 15 years in jail, a small price to pay for such a heinous crime.

In addition, prosecuting paedophiles and child abusers in Malaysia is difficult due to the common citizen’s lack of awareness and a culture that encourages “hushing up” these kind of events. The arrest of paedophile Richard Huckle last year caused massive outrage when it was revealed that he had managed to sexually abuse hundreds of young children before getting caught.

Unfortunately, the current laws are not enough to shut down all the traffickers working in this day and age. While the Child Act and Penal Code covers physical harm or abuse, some crimes fall into a gray area which makes it harder to prosecute.

The main problem is that while the government has signed the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), Malaysia has NOT implemented the Optional Protocol on the sale, prostitution and pornography of children. There are also currently no laws concerning crimes conducted against children online, which is concerning as children are particularly vulnerable to online predators who may sexually “groom” the child without ever meeting them in person.

In an interview with R.AGE last year, Unicef Malaysia representative Marianne Clark-Hattingh noted that legislation in Malaysia needs to be updated in order to keep up with the rapid development of communication and multimedia technology.

“Online abuse and exploitation most often takes place in the deep privacy of the mobile phone, the computer, or any other electronic device. It can move anonymously from the private to the public sphere, and across countries and borders, quickly,” she said.

What can you do to help put a stop to this odious industry?

For a start, you can sign the petition below from the Citizens Against Child Sexual Abuse calling for new laws and harsher punishments to be set up. By pressuring the government to act, we can send a stern message against child abusers and traffickers and stop them in their tracks.

And then, share this video and article because raising public awareness and admitting that we have a real problem in our own backyard, is the first step towards fighting this uphill battle.

“You may choose to look the other way but you can never say again that you did not know.”

William Wilberforce

Produced by Megan C. Radford and Shufiyan Shukur

In 2010, ninety-one babies were abandoned by their mothers in drains, washrooms, mosques, and other public places in Malaysia. Then, in the first week of 2011 alone, seven babies were abandoned, an average of one a day.

Experts say that the main cause of Malaysian baby-dumpings is the stigma that young unwed mothers face from the conservative Muslim community.

Even health care providers have been reported to demand marriage certificates from women in labour, to prove that their children are legitimate.

Girls are sometimes no longer welcome in their homes or families when they become pregnant. Under this kind of pressure, many feel that the best way to deal with their unwanted baby is to get rid of them as quickly as possible.

Malaysiakini spoke to two NGOs and the office of the Minister of Women, Family and Community Development to try and get a handle on what these young girls go through, and what is being done to help them and their fragile newborn children.

Share this