The earth doesn’t need us

What happens when human race suddenly disappear?

How does it make you feel?

What happens when human race suddenly disappear?

How does it make you feel?

Women of the Mah Meri tribe wearing a traditional clothes before preforming traditional dances on Pulau Carey beach.

Members of the Mah Meri tribe walk towards the beach to begin the ceremony – the Hari Moyang Puja Pantai festival to celebrate the spirit of their ancestors.

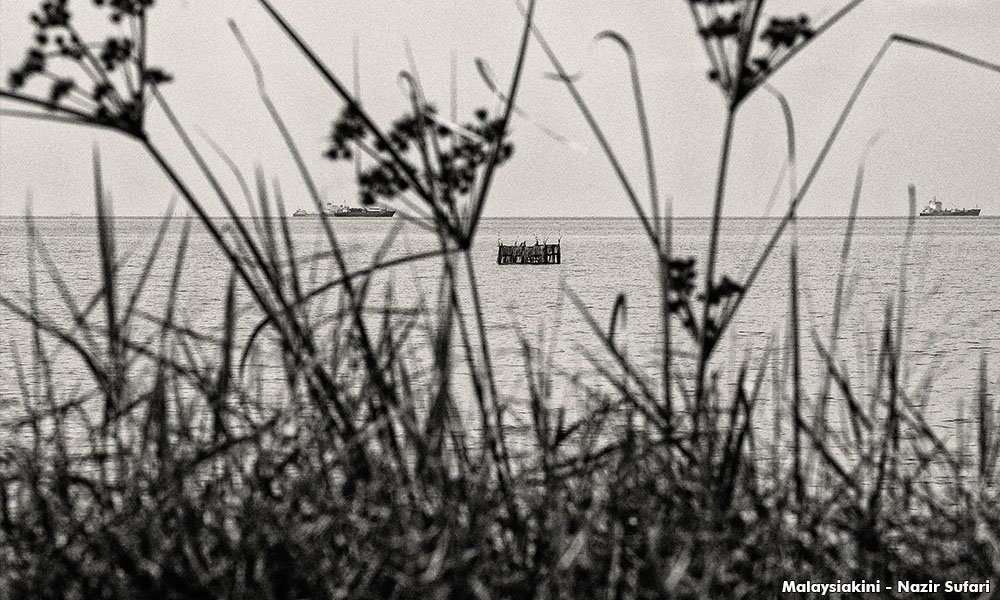

An altar erected during lowtide for the ‘Puja Pantai’ ritual at a beach in Pulau Carey. In the background is the Straits of Malacca which is one of the busiest straits in the world.

Members of the Mah Meri tribe and tourists waiting near the beach for low tide in Carey Island.

Members of the Mah Meri community perform traditional music during the ‘Puja Pantai’ ritual, which is to celebrate their ancestors.

Members of the Mah Meri tribe apply make-up and make final preparations on the beach before performing a traditional dance.

Members of the Mah Meri tribe perform a dance at Pulau Carey.

Faces of the Mah Meri people in Pulau Carey before the ritual starts.

The altar erected near the beach for the ‘Puja Pantai’ ritual.

A shaman from the Mah Meri tribe on a shrine erected for the ‘Puja Pantai’ ritual.

A Mah Meri shaman stands on the beach during the Hari Moyang Puja Pantai festival at Pulau Carey.

A Mah Meri tribesman siting while in a trance as the spirit of a Moyang enters his body.

A portrait of a Mah Meri tribesman with a wooden mask which he wears when he performs the ‘Main Jo-oh’ dance.

Smoke from the burning incense to summon spirits.

A Mah Meri Tok Batin (village elder) during the ‘Puja Pantai’ festival.

Mah Meri tribesman mid-dance during the festival.

Mah Meri men assisting a fellow tribesman who was in a trance, during the ritual.

The ‘Puja Pantai’ ritual, viewed from afar.

Members of the Mah Meri tribe leave the beach after the ‘Puja Pantai’ ritual ends.

Will this tradition be maintained by the younger generation so that it can be passed on to their children or will it be lost through modernisation?

All is not peaceful in the woods and forests of Kelantan. An “uprising” of sorts is in the works, after years of simmering disquiet over rampant logging, that threaten the livelihoods and culture of the local Orang Asli.

This was conveyed to me by one of the natives, who hosted me during my recent trip into the hills of Gua Musang. An Orang Asli from the Temiar tribe, who is personally involved in the timber blockades set up to stop loggers, from encroaching into their customary land.

My host served a simple but delicious meal for lunch on the day of my visit. This is symbolic of the hospitable nature of the local Orang Asli, as well as a stark reminder of what they stand to lose, if the forest around them continue to be cut down, uprooting them from their way of life and source of sustenance.

There was roasted tapioca, fish, jackfruit, and more, with a helping of rice and sweet tea to wash it all down. His cat meowed incessantly and miserably from the adjacent room – begging to be let out to join the feast.

However, the mood around the floor (there was no table) was sombre, as my host Anga Anja, 42, pondered over whether his two grandchildren would be able to cook such a bountiful meal in the future.

Anga hails from the Temiar village of Kampung Barong, Gua Musang, and the land around him is threatened by deforestation. And the worry and anger over how this may impact their future, has stirred up the normally docile Orang Asli.

“We have awakened,” he said. “We have awakened and we are sad. How are our grandchildren supposed to live in the future? I could pass away at any time, but how are our grandchildren supposed to live after us? That’s why we have awakened.”

According to analyses of satellite imagery compiled by the Global Forest Watch, Kelantan had 1.2 million hectares of tree cover in 2000. By 2014 however, nearly 30,000 hectares of that (20.9 percent) had been lost.

“It’s not even far away. It is just nearby, there are logging areas all around us. Yesterday they (loggers) said they want to cut down everything. It’s a forest reserve, they said,” Anga related.

In the grand scheme of things, this could seem mediocre compared to the rate of deforestation seen elsewhere in the country.

At the national level, the loss of tree cover over the same period is at a comparable 19.1 percent.

Kelantan’s loss of tree cover also pales in comparison to that of Negri Sembilan, Johor and Malacca, which occupy the top three positions (33.9 percent, 31.5 percent, and 30.3 percent respectively) in Malaysia.

But then again, watching green pixels on Earth turn Martian-red from space does not tell the whole story.

For Anga and his fellow villagers, the effects of deforestation on their culture and livelihood is clear and ever present, something that we, as visiting outsiders can perhaps only understand if we see it with out own eyes.

Kampung Barong was the first stop of my trip, after spending the night at Kuala Lipis and leaving the luxury of driving on paved roads.

Reaching the village entailed covering almost 50km. The average passenger car would take half an hour to cover such a distance on the highway, but this trip took three hours over muddy roads and across rivers in rugged four-wheel drive vehicles.

The journey also took me and my videographer through vast swathes of land that had been recently cleared to make room for oil palm plantations, before we finally reached the jungle proper.

The tale of the Orang Asli disquiet is probably better told by the broken and muddy landscape we saw along the way. Land which used to be hallowed burial grounds, bountiful orchard groves and favourite hunting grounds.

The driver of the 4WD vehicle that brought me there said he was thankful we were never caught on the road with anything worse than a drizzle. Otherwise, even these these rugged off-road vehicles and their intimidatingly large tyres with deep threads, would get stuck in the mud.

At least that’s what he would tell me when he was not busy expressing his shock, over the land that used to be lush and verdant green during his last visit just a couple of years ago.

He was keen on staying out of trouble, so I won’t be identifying him, and he would be steering clear of both the Orang Asli’s and the Forestry Department’s blockades to avoid any possible confrontations.

As soon as we met, Anga was more than eager to recount how he and his fellow villagers first encountered the Kelantan state government’s poverty eradication programme Ladang Rakyat, which is similar to the federal government’s Federal Land Authority (Felda) settlement scheme.

It was about seven years ago. The time was about around 4pm.

Anga and some other Kampung Barong villagers had gathered at the crossroads just outside their village to wait for their ride, on their way to attend religious courses.

“Then around five o’clock, we heard the buzz of chainsaws near the steel bridge. It was the first time this has happened, and, hey? Why have they gone into the cemetery? They (foreign workers and a local contractor) had set up camp there.”

“After hearing the sound of the chainsaws, my friend went over. He found a lot of vehicles parked there, so he went over and asked, ‘Sir, how did you get here?’”

The friend found out from the workers that they were there to clear the land for the Ladang Rakyat programme. He objected, stating that the land they were cutting down for firewood was a cemetery, and the surrounding area were groves tended by the Orang Asli.

But the contractor leading the gang of workers would hear none of it, and rudely rebuked him.

“No way! These are not Orang Ali groves. Your groves are up there in the mountains. The durians are not planted by you. It’s (from) bear poop,” Anga recounted the contractor’s purported words.

He said his friend then returned to the group and told him and the others what transpired.

After they returned from their courses, the villagers met.

“We thought and thought about it. There used to be just loggers. They destroyed the trees, but we didn’t know better.”

“Now we do,” he said, relating how the local community decided that it is time to act, as their culture and livelihood is at stake.

The first anti-logging blockades went up in January 2012. Some 300 Orang Asli from 31 villages in Gua Musang took part, claiming that their ancestral land is being taken by the state to be given to logging companies and for its Ladang Rakyat programme.

The blockade was the first of its kind in Peninsular Malaysian and continues to be a running battle between both sides today. Then, as now, the blockades are being continuously torn down by authorities and put back up by the Orang Asli from time to time.

The Temiars had also taken the Kelantan government to court over the alleged violations of their customary land.

The state government had alleged that the Orang Asli’s resistance were instigated by outsiders. Their lawyer Siti Kasim was even accused of championing the indigenous community’s cause, just so that she can fight with the PAS-led Kelantan government.

“This issue in Kelantan is driven by political parties, working with those who oppose the implementation of Islamic laws such as Siti Kasim who is against the Kelantan state government, not an environmentalist and certainly far from being someone who cares about the Orang Asli,” PAS working central committee member Muhammad Sanusi Md Nor reportedly said last December.

However, all of the Orang Asli folk that I interviewed during my trip to Gua Musang – each in a different village – vehemently denied this. Instead they stressed that the initiative was their own.

If anything, the much-demonised ‘outsiders’ served as a moderating influence in the Orang Asli’s resistance and kept their campaigns non-violent.

“We fight with our mouths, with written letters. (Fist) fights, guns, adzes, blow darts are all left behind. We follow the law, the demand through the law, and we fight through the law,” Anga said.

His sentiment is echoed by the Pos Balar village chief Alek Busu, whom I met outside his home the following day.

He told me that the choice to fight is their own, but others had provided advise on the course of action to take.

“There is no outside influence. We merely sought their views on what we can do; things we can’t do, we don’t. The outside has no sway over us. Nothing.”

“The outsiders merely offered advice: If you want to claim this land, do it properly, do it by the book. This method is legal, because it doesn’t cause damages and all that nonsense. We follow the law, we go through the courts.”

“That was our decision,” he said.

Fresh from a hunt with a machete and a knife strapped to his belt. Alek too shared his anxieties about the depleting resources in the forest that they forage from, and the perceived trespass of their customary land.

“We set up the blockades because we have a stake in this logging, which we think is not right. It intrudes on our customary land, and all our livelihood is gone, destroyed. The Ladang Rakyat too, because they do this without the consent of the villages or anyone.”

“They don’t ask the chairperson (of the village committee) or the chief. No respect. So now we are deeply disappointed.”

“When the rainy season comes, we suffer. Back in 2014, three kids died because of the floods. The floods are the reason why we don’t like logging, because it disrupts our lives and livelihood.”

“The plants in the forest are all gone, like our fruit trees. It’s hard to find anything, and that’s why we set up the blockades. We don’t like it,” he said.

The Kelantan Menteri Besar Ahmad Yakob had previously denied marginalising the Orang Asli. On the contrary, he said, the state had looked after their welfare.

He said the state government had gazetted 973 hectares of land as Orang Asli reserve, and another 19,000 hectares for them to roam about in the state.

Notwithstanding the state government’s efforts, however, it appears that a lack of engagement had worsened the conflict between the state and the Orang Asli.

“This issue should not be raised. The Orang Asli community in Kelantan is only about 10,000 and the area should be sufficient and need not be raised again,” Bernama quoted him as saying in a Dec 4 report last year.

According to Alek, the Orang Asli had tried to bring their grievances to the

Meanwhile, as the tussle between the Orang Asli and the state continue over the land and blockades, Anga shares his idea of what a good life looks like.

“They said that these matters should be referred to the Orang Asli Development Department (Jakoa). When we met Jakoa, they said this is the Forestry Department’s matter. When we met with the Forestry Department, they refer us to the state government,” he said.

He said one company involved in the Ladang Rakyat project offered his village RM10,000, purportedly with no strings attached. Though the money was turned down, as they preferred to keep their forests with which they can earn their keep, instead of receiving a one-off windfall, and losing their ancestral lands.

“We can count the money another day. But as long as we have this land and this forest, we can make bracelets and sell it in shops and so on to make some money.”

“Yesterday for example I went to catch fish. People ask, and we go fishing. I brought him there, and he asked, ‘Hey, go catch some fish. I want to eat’. I went, cast the net, brought it to him, and he gave me RM20. Enough. That would be nice.”

“If we were to take the (RM10,000) money just like that, we don’t want it. We don’t want to owe anyone anything,” he said.

Note regarding tree cover data: Not all tree cover are forests and the tally merely represents the presence of trees with canopy cover above 30

The figures are cited here as a proxy to the extent of deforestation, legal or otherwise, from an independent source.

The Global Forest Watch also provides data on tree cover

Share your view on this issue.

Video by World Economic Forum

Expected or not?

Year 2017 is supposed to be Visit Pahang Year but instead of attracting tourists enjoy what Cherating has to offer, people are forced to take a short drive across the border to Kemaman, in Terengganu, where the happenings are.

The beaches in Cherating are indeed a spectacular sight. Although without going into the sea when the tides are high and the red flag is up, just being able to sit by the beach and listening to the waves is already so relaxing.

This is why I have always fallen in love with the beaches here since visiting the Legend Cherating on several writing assignments back in the 1990s, I have not been back to Cherating until this long holiday to show my children places that I have visited in the past.

Over 20 years, Cherating has never changed. The town is basically still the same with the old hawker stalls along the East Coast Highway, with not much improvement or anything to really shout about.

We tried out the local restaurant but decided that we would not visit the same stall a second time. Instead, we decided we would try out the famous Tong Juan seafood restaurant in Kemanan on the second night.

Disappointingly, I have to say that several of the places that were the highlights in the 1990s are now gone.

One of the batik proprietors could only say,

“ Cherating is a dead town during off peak seasons ”

But when exactly is peak and off peak seasons? Most local tourists would prefer to avoid these places during peak seasons. Interestingly, on the first night that we were there, the hotel was fully booked. There were both Malay as well as Chinese local tourists visiting Cherating.

For us, Cherating is just a three-hour drive from Kuala Lumpur. When we love the place, we can come during off-peak seasons and just enjoy the sea and the beautiful beaches.

Imagine what a big disappointment it must have been to many tourists who come this way and go back, not enjoying their holiday in Cherating to the fullest.

Using the Waze to locate the handicrafts complex was also a disappointment, as the building no longer hosts the handicrafts. I told my children that it could have been converted into a school of hospitality. But where then is the handicraft complex? Nothing seems to appear on the map although Pahang Tourism mentions about the complex.

Along the way there are only a couple of small batik painting shops. I remember back in the 90s, there were some bigger workshops with lots of batik painters. Tourists were flocking to this batik outlet to see how the batik handpainting is done, and some bought the batik to bring home along with them.

The next big thing in Cherating is the turtle conservation. It is a great place to educate the young people about conserving the leatherback and hawksbill turtles.

The turtles are now considered endangered species, but the place has not changed very much since 20 years ago. The State tourism should at least have provided educational guides to talk to people about the turtles or project some video on conservation efforts undertaken by the government. Nothing of that sort is being done!

It is the same old pools with turtles in them. There is one area that we merely assumed to be the turtle eggs hatchery, as signboards were not even placed there to explain to children how long it normally takes before the eggs are hatched. How do you expect the public to learn and appreciate turtle conservation if the explanations are not given?

Despite attracting so many local and foreign tourists, no one was there to even sell drinks or ice cream. We would have enjoyed some coconut drinks if they were sold here at prices we could never get in Kuala Lumpur!

I believe a lot could be done to improve the charms of Cherating if only the Pahang State Government gives it some attention, instead of being busy approving the bauxite mining and the Lynas rare earth mining company.

Deep sea fishing for fishing enthusiasts: Despite the high tides, some tourists would love to go out into the sea, provided that there are bigger boats that are safe to go out into the deep sea.

I remember years ago, the general manager of Legend Cherating took me out into the sea to watch the seagulls. It was a fascinating experience.

The Best of Cherating Food: The state government should put together some of the best hawkers in one location for people to enjoy the local cuisines. At the moment, there appears to be just one famous item to bring home – the keropok lekor. Besides that, what else can tourists enjoy while visiting Cherating?

Kite Flying: The beaches here are beautiful, but if we cannot go into the sea, where can we find the kites? Where can we find a place where we can show the children how to play tops? Forget about the karaoke, where in Cherating can we find a place at night to show them what a wayang kulit show is like?

Pahang Tourism and the state exco for tourism should do more work to promote Cherating especially during its “off-peak” seasons. People do like to come to Cherating during the long weekends, and not only during school holidays.

We ended up staying in beautiful Cherating but spending our money in Kemanan. It is such a big contrast between the two border towns. One is well-developed, the other clearly shows a big neglect by the state government.

One highly recommended restaurant is Restoran Kopi Hai Peng. Although it is a simple restaurant, it has a history of over 76 years.

The restaurant was started in 1940 by 102-year-old Wong Sang Hai, who arrived from the province of Hainan in China. The restaurant is the equivalent of Restoran Kow Poh in Bentong, which offers the famous Bentong ice-cream.

Here, it is like a muhibbah coffee shop, because people of different races sit together under one roof to enjoy the patriarch’s specially brewed coffee and roti bakar. They have since added the nasi lemak, the laksa and a number of other local cuisines.

Prices are still reasonable. This is important as tourists do not like to feel they are being slaughtered when they eat here.

The place is kept clean and presentable. A local person, for example, would not hesitate to bring foreign tourists to try out the coffee here because it is still affordable.

I must commend the grandson of the Wong Senior, Richard Wong is able to keep up with the times. One cannot visit Kemaman without trying out the coffee in Restoran Hai Peng.

Kemaman is also famous for its fisherman’s jetty where people can buy the fish straight from the day’s catch. There are also a number of homestay chalets in Kemaman, which we may try out on our next trip here if Cherating no longer offers all the attractions one would expect.

Desa Aman Puri is like a melting pot and a haven for various types of gastronomical delights.

From the authentic Italian cuisines served at Bel Pasto Italian Pizza and Tak Fook Hong Kong Seafood Restaurant to the famous Hakka Lui Cha at the Big, Big Bowl Cafe and Indian Nasi Beryani at Anuja Restaurant, Aman Puri has a lot to offer to people, both to the locals and those living in the Klang Valley.

Although it is a mere 10-minutes’ drive from One Utama heading towards Bandar Sri Damansara at the tail end of the Puchong-Damansara Highway (LDP), the prices of food here are far more reasonable by comparison to restaurants in Petaling Jaya.

The restaurateurs here have to learn that if they raise their prices, especially after more people flock this way, they will no longer be attractive be attractive to foodies from Petaling Jaya and beyond.

In the past few years, the place has become popular for all kinds of cuisines, with more new restaurants such as Restoran Fei Fei Crab and Restoran Lan Je being set up here. The original Fei Fei Crab is in Petaling Jaya, while the first Lan Je restaurant started in Rawang.

Those that fail to maintain their standard or where the food is pricey simply do not survive here due to very tough competition not only within Aman Puri but also from other restaurants within a radius of 5 kilometers.

A number of restaurants have come and gone, but the ones that survive more than a year are doing well.

Nancy Choo, 63, for example, used to operate a stall in Aman Puri where most people know her as Auntie Nancy’s eatery. Since closing down her stall, she has joined forces with her daughter, Angie Lim, where the mother-and-daughter pair has a bigger variety to offer at Lim’s Big, Big Bowl Café. Choo has a strong following; therefore, her presence at Big, Big Bowl has helped to boost the business a lot.

Judging from the photographs in their Facebook page, Lim also was operating a successful business when her restaurant was previously based in Kepong.

Nancy Choo, 63 and her daughter Angie Lim

One of the dish from Big Bowl

Apart from their signature dish, the Hakka lui cha, I like Lim’s fish fillet noodles and her pan mee. Her laksa noodles is also good and worth trying. What is interesting is that her noodles are all hand-made. I have yet to try her mother’s cooking. I will do it when I travel in that direction.

Adjacent to Lim’s Big, Big Bowl Café is Love Earth organic restaurant, which is also worth checking out especially its Taiwanese soup noodles. However, most guests may not like their self-service concept, which is sometimes a big letdown especially when there are hardly any other clients during off peak hours.

For the crabs, both Tak Fook and Fei Fei come to mind. During special promotional seasons, Tak Fok for example can offer crabs at RM25 a kilogramme. The owners are a young couple from Hong Kong. This is their original restaurant, where it is mostly packed at night.

Restoran 168 specialises in both dry and soup pan mee but surprisingly, despite pan mee being a very common dish, the place is often packed in the morning. Just behind is the Penang Chew Jetty where the proprietor once operated from a small stall in Aman Puri.

One of the dish from Bel pasto

The best restaurant in my opinion is still Bel Pasto, operated by one Italian chef, who prefers to be known only as Sam.

This restaurant is famous for its authentic Italian cuisines because the chef is Italian himself and very passionate about his food. Try his Tiramisu, and comparing his prices and the quality to other café, it is value for money! Every time I introduce guests here, they give him the thumbs-up!

Bel Pasto is the kind of place I would bring my foreign guests. A year ago, when I had some visitors from Canada along with their children, they enjoyed the food so much that they decided to give us a treat in return at the same restaurant.

Food is good, but…

Like in most other places around the country, Desa Aman Puri needs a good facelift.

Alfresco-style seating may be popular with Malaysians who prefer the street food to posh restaurants, but having huge but ugly looking canvases will not do a lot of good to guests from overseas. It is

Rubbish is also strewn all over the place and some drains remain uncovered after the concrete slabs used had been removed. If properly covered, some of these public drains could provide some useful parking spaces.

Selayang Municipal Council Zone 23 councillor, Ng Wei Keong, has promised that he will look into the facilities and the cleanliness of the place, but it may take a while before the local council staff work on improving the area.

The state government has sponsored the bins; they should therefore keep their own places clean.

With a little effort from the restauranteurs and the public perhaps to keep the place clean, Aman Puri can become a haven for all the salivating food lovers.