San Francisco (AFP) - Silicon Valley on Wednesday was mourning a pioneering computer scientist whose accomplishments included inventing the widely relied on "cut, copy and paste" command.Bronx-born Lawrence "Larry" Tesler died this week at age 74, according to Xerox,...

Blind; but doesn’t lose sight on the importance of education

Blind; but doesn’t lose sight on the importance of education

Born in Besut, Terengganu in 1961, at the age of seven, Mah Hassan was sent to pursue his primary education at Johor Bahru’s Princess Elizabeth special school for the blind – a train journey which even today would take up to 17 hours from Wakaf Baru in Kelantan, the nearest station to his hometown.

By the time he entered secondary school, Mah Hassan has integrated into the mainstream system where one or two visually impaired pupils will be placed in an ordinary classroom with other sighted students.

During an interview held at his law firm in Sentul, which is also the office for KL Braille Resources, Mah revealed how his father had fought societal norms and approached the Welfare Department for assistance to provide him with an education that would help him to lead an independent life.

The law graduate from Universiti Malaya went on to earn his master’s degree at Southampton University, United Kingdom, before returning home for a 13-year stint with the Kuala Lumpur Stock Exchange. In 2005, he left to set up his own law firm.

The early realisation that education is the key to assisting people with disabilities has shaped Mah Hassan to be an advocate for their rights to equal access to information – including pioneering a project to produce a braille version of the Quran.

At the age of 56, Mah Hassan is a father of six – three girls and three boys – the eldest three of whom are pursuing their higher education.

He has set many personal records and aims to inspire others like him.

Here is Mah Hassan’s story in his own words:

AS A YOUNG BOY, I WAS SO ENTHUSIASTIC TO GO TO SCHOOL. But for my parents, as I understood it, it was very challenging.

They had to face the reality of how to part with their blind boy. Also, the people and neighbours accused them of them being irresponsible.

My father told me every time I leave the house to go to school, he could not follow me. He always thought about what the people were saying.

My mother will send me because my mother is stronger in that sense.

FOR ALL PARENTS OUT THERE, I wish to urge all of you who have children with disabilities, give your children an education.

With education, you are giving him or her the important equipment to live independently.

You can give them as much money as you can afford but the money will go. If you give them education, it will stay with them forever.

IN ADDITION TO ACADEMIC SKILLS, I always see that primary education provided me with an important background, basic skills that prepared me to lead an independent life. In other words, being a blind person, we were taught how to groom and take care of ourselves. How to live independently.

For every blind child, I see survival skills as a very important factor. Because even with academic success, without the necessary guidance, from my observations it would be very difficult to survive in life.

COMPETITION WAS STIFFER DURING SECONDARY SCHOOL. I managed to continue until Form 6, before pursuing my degree in law at Universiti Malaya. As a matter of fact, I was the first blind person in the country to take up law.

When I was called to the bar in January 1989, again I created a Malaysian record as the first blind person in the country to get legal certification as an advocate and solicitor.

Why do I stress on the records? Because the greatest challenge for blind students is a lack of books.

I PRACTICALLY DID NOT HAVE ANY BOOKS AVAILABLE IN BRAILLE. So I had to double my efforts.

I spent the greatest part of my time in university to transcribe books into braille. During my school time, the blind at the time did not even have any copy of the Quran in braille.

The Quran is the basis for Islamic books so I think it is a denial of our right to have equal access to the Quran.

BESIDES STUDIES AND PROMOTING MY LEGAL PRACTICE, I was also active in NGOs that provide services for the blind.

I was president of the Society of the Blind in Malaysia from 2000 to 2010. I am also co-founder of the Malaysian Blind Muslims Association and served as president from 1989 to 2002, before I resigned for the benefit of younger leaders.

Now I am still active in the associations but perhaps to a lesser degree.

IN 2002 WE COMPLETED THE DRAFT FOR THE PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES ACT. I headed the technical working committee and the Act came into force in 2008.

It was a five-year process. It took quite a while because in 2006 the UN came out with the first international convention on rights of people with disabilities, so we have to fine-tune our proposed bill.

I was given the privilege to represent the country at the UN in 2006 when we negotiated for the convention.

MY EMPHASIS IS MORE TO PROMOTE THE RIGHT TO LITERACY AMONG THE BLIND. The rights for blind people to have equal access to reading materials in braille.

Be it for education or any other pursuit. Our focus is mainly on transcribing Islamic religious books as well as academic books.

We believe these two genres have been sidelined.

WITHIN ONE WEEK OF MY ARRIVAL IN THE UK IN 1991, I WAS GIVEN A COPY OF THE BIBLE IN BRAILLE FOR FREE. It gave me a challenge.

If Christian voluntary groups can work to give free Bibles, why can’t we Muslims provide free Quran? So that’s what I tried to do.

When I came back to Malaysia, we worked on a research project to produce the Quran in braille and now we have the capacity here at KL Braille Resources.

In order to finance the project, I launched what we called the Wakaf Al-Quran. We invite the public to sponsor any number of Quran as they wish and each set is priced at RM250.

With this sum, we finance the production of the Quran and distribute them to the needy.

I HAVE LOVED CHESS FROM A YOUNG AGE. I see chess not only as a competitive activity but for any disabled or blind person, it can also provide you with an opportunity to integrate with normal people.

EVEN THOUGH I AM BLIND, MY UNIVERSITY’S TEAM ACCEPTED ME JUST LIKE ANYBODY ELSE. I had taken part in an open tournament for selection for the university’s team.

I was the only blind person there. But I competed against sighted people and got third place.

They needed four people to fill the team. I also played in the UK’s chess league.

FOR THE 2009 AND 2010 PARALYMPICS, I WON GOLD FOR CHESS. Another achievement was in 2003 when I took part in the ASEAN Chess Championship for the Blind in Mumbai, India, and won second place.

Now I am still president of the National Chess Association for the Disabled and our members are busy preparing for the forthcoming paralympic games in Kuala Lumpur in September.

The current chess set produced by KL Braille is also being used exclusively for the paralympic games.

WHEN BLIND PEOPLE PLAY WITH SIGHTED PEOPLE, both players have to announce their move. The board is modified to allow for usage by blind people.

But we don’t compromise on the rules. There is no difference to the rules.

The black and white pieces, how a blind player can tell is based on touch.

BE IT VISION 2020 OR TN50, I wish to see that disability issues are not sidelined. The way I see it, disabled people should be given equal rights with other citizens.

They are not to be discriminated against or left out. They should be given all opportunities.

The movement to promote equal rights has been talked about since 1981.

IN THAT SENSE WE HAVE SEEN MUCH PROGRESS, but in some other areas, the progress is too slow. For example, we have difficulties with financial institutions.

Just to open bank accounts, have I always received grievances from my blind counterparts. They wanted to open bank accounts but are not allowed to by certain banks.

DISABILITY ISSUES ARE OFTEN NOT GIVEN ENOUGH COVERAGE. The media are prone to focus on issues that can trigger sympathy.

When you talk about disabled people, I think it is more worthwhile to talk about rights rather than individual challenges.

When doing a story, just ask yourself, who will benefit?

If it is just one or two people, how many stories do you want to do?

THE MEDIA RARELY HIGHLIGHT STORIES FROM THE OKU’S PERSPECTIVE. They will take a third person’s view.

If you want to talk about the problem of beggars, those selling tissues on the streets, just go and talk to them.

If authorities want to catch them for selling tissues, the first thing we must ask is, have we given them opportunities to make a living?

OPERATIONS TEND TO INCREASE WHEN THERE ARE BIG PROGRAMMES PLANNED. For example, if the prime minister is coming, they will be detained and put into trucks, sent off somewhere and asked to find their own way home.

If the breadwinner is arrested, how will those left at home survive?

Maybe the spouse will take the children to go out and beg.

WHEN THERE ARE NO JOB OPPORTUNITIES, what other choice do they have, at a time when even healthy able-bodied people are finding it difficult to find jobs?

What do you expect?

MALAYSIANS ARE VERY CARING. I don’t dispute that. But when it comes to giving disabled people their rights to lead independent lives, that’s when the problem starts.

For example, when you want to ride the LRT, the public is very caring. I don’t think we have any big problem anymore. The awareness is there.

But do you know that for people using wheelchairs, to have access, is it still very difficult? That is their right.

BEING BLIND IS NOTHING TO BE SHY ABOUT. As a matter of fact, we want to be treated just like any other ordinary people.

People often call us “golongan istimewa” or “kelainan upaya” (differently abled).

The term “orang kurang upaya” (disabled) shows that we have a disability but we are not pampered.

TREAT ME JUST LIKE ANY OTHER OF YOUR FRIENDS. If you can joke with and tease them, do the same to us.

What is the difference? We are the same. Just that it has been fated that we lost one of our senses.

VOX People

Silicon Valley inventor of ‘cut, copy and paste’ dies

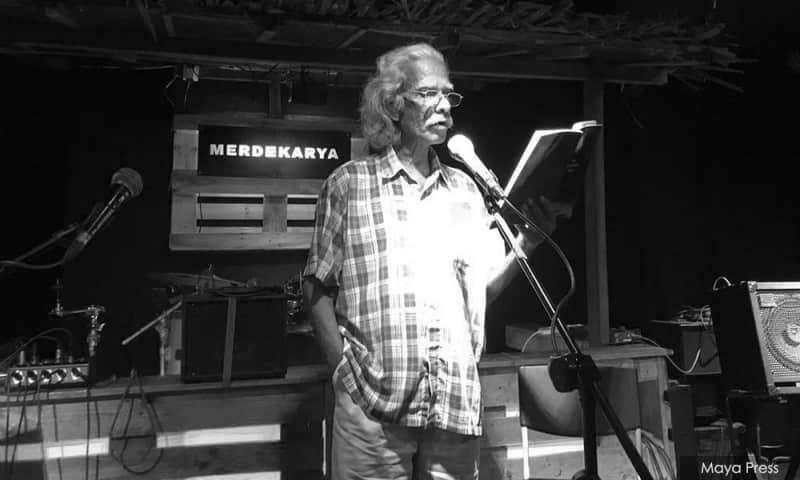

Veteran writer KS Maniam mourned by literary community

Tributes are pouring in for veteran writer KS Maniam who passed yesterday aged 78 at the Universiti Malaya Medical Centre.Born as Subramaniam Krishnan in Bedong, Kedah in 1942, he succumbed to cancer of the bile duct.His novels included The Return (1981), In A Far...

Afghan artist brushes aside disability to open arts centre

Kabul (AFP) - Unable to use her hands, arms, or legs, Afghan artist Robaba Mohammadi has defied unlikely odds in a country that routinely discriminates against women and disabled people.Denied access to school, as a child she taught herself to paint by holding a brush...