Malaysia’s rhinos: The long goodbye

Malaysia’s rhinos: The long goodbye

Tam’s is a story reminiscent of that of 45-year-old Sudan, once the world’s last surviving male northern white rhinoceros. Named after the country of his birth, Sudan was put to sleep in March 2018 at his home at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya.

Sudan’s death and the photos of his final goodbye with his tearful keepers pulled at the world’s heartstrings and, for a moment at least, he became the gentle, wrinkly and horned face of the terrible toll poaching is taking on the world’s fast-shrinking wildlife.

In our little corner of Southeast Asia, in the dark, tropical jungles of Sabah, Malaysia’s own tragic tale is playing out. Just last month, we bade farewell to Tam the rhino. Seeing such a magnificent creature take his last breath cut to the quick, but hurt even more to know that old Tam, brought to the Tabin Wildlife Reserve in Sabah in 2009, was Malaysia’s sole remaining male Sumatran rhino.

Tam’s death leaves grand dame Iman the last of her kind on Malaysian soil. The line ends there. All hope of breeding Tam with Iman or two other females, the late Puntung and Gelegup, dissipated when the three females were unable to breed.

The two-horned Sumatran rhino – the smallest in the Rhinocerotidae family, aka the rhinoceroses – is “critically endangered” according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Once found roaming the forests and swamps of China, India, Bhutan, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, Bangladesh, Malaysia and Indonesia, there are less than 80 animals left in the species, clinging to life in the wilds of Indonesia.

Former range

Current range

In Malaysia, it’s game over. Despite the best efforts of authorities and conservationists, the Sumatran rhino – both the Western and Eastern subspecies – has been extinct in the wild here since 2015. So, how did Malaysian get it so wrong with these odd-toed ungulates?

Losing a species

Decades of poaching and habitat loss from logging, development, human encroachment and farming have all steadily eaten away at the rhino population. It’s no surprise that habitat loss has taken its toll – between 2000 and 2012, Malaysia reportedly had the world’s highest deforestation rate, at 14.4%.

Meanwhile, the foolish use of rhino horns in traditional medicine has fuelled the illegal trade that has contributed to driving the animals to extinction. Poaching is believed largely responsible for the massive dip of 70% of the world’s Sumatran rhinos population in just 20 years.

Now, with so few animals left and the population so scattered, National Geographic deemed isolation the “single biggest threat” to the species. Cows, as female rhinos are known, give birth about every three to four years, but that period could stretch considerably longer as their numbers dwindle. Females, as suspected in Iman’s case, develop cysts and fibroids in their reproductive tracts if they go too long without mating, further complicating matters (it’s called the Allee Effect).

With no luck in breeding Tam, Malaysia attempted to bet on assisted reproductive technology (ART) to enable exchange of reproductive cells with captive Sumatran rhinos in Indonesia. However, WWF-Malaysia in a statement, said despite high-level diplomatic engagement in 2015, “ART efforts have yet to take place.”

Tam the rhino. Photo by: Raymond Alfred/WWF-Malaysia

The final battle

With Iman all that’s left of the species in Malaysia, all conservation efforts are now trained on neighbouring Indonesia. A collaborative effort, the Sumatran Rhino Rescue, is underway to capture the few wild Sumatran rhinoceroses that remain, to afford them greater protection and for breeding.

This is the end game and authorities and conservationists in both countries know there’s no snapping of fingers to make things right. Every step is crucial. Pahu, a female caught in Borneo was even afforded a police escort to her new home and bulldozers to clear the way.

WWF-Malaysia, meanwhile, says ART is still possible and wants Malaysia to enhance diplomatic efforts with Indonesia. Both countries seem to be taking heed; they plan to pen a memorandum of understanding on the Conservation of the Sumatran Rhinoceros, and will discuss the possible application of ART.

Description

- Smallest of the rhino family.

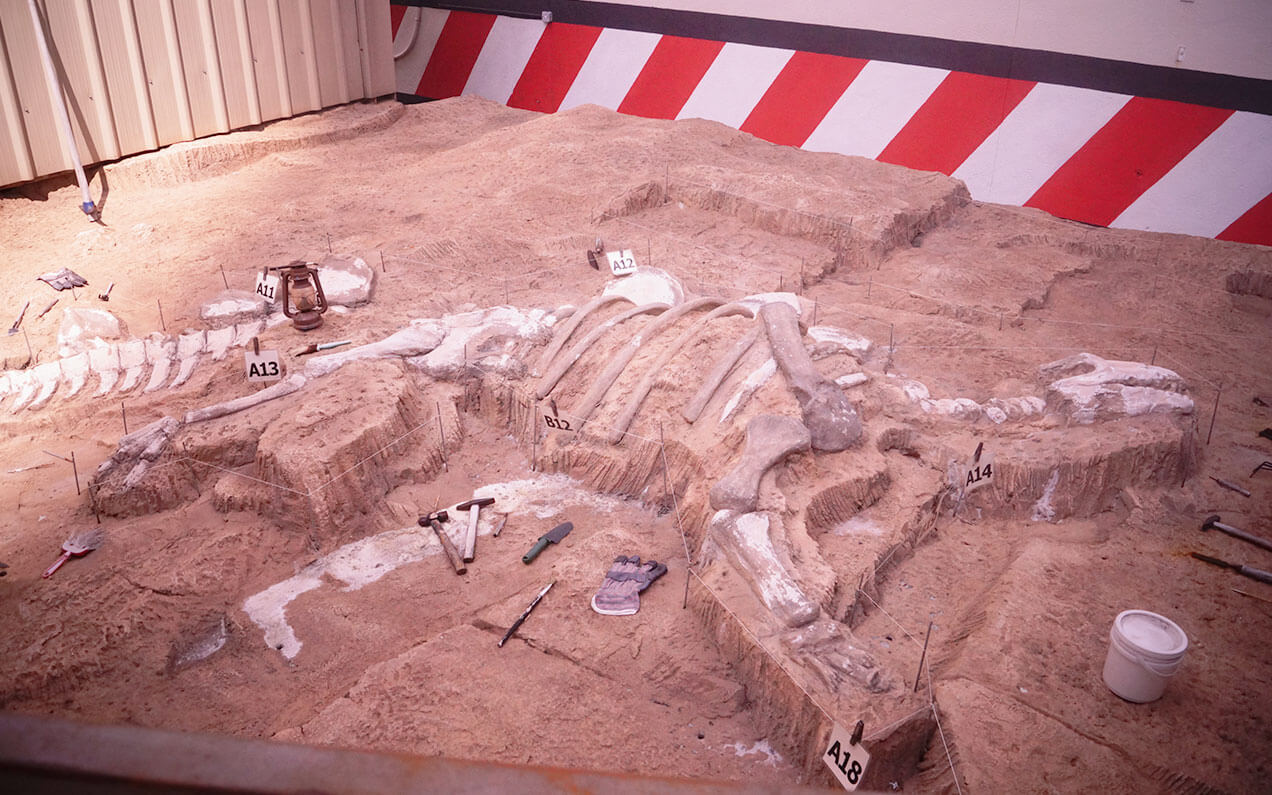

- More closely related to the long-extinct woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis), it’s also the hairiest.

- One of three Asian rhino species.

- Mostly solitary, found in dense tropical forests.

- Can live between 35 – 40 years, weigh up to 950kgs, and grow to 5 feet high and 9 feet long.

- Females give birth every 3 – 4 years.

Survival

- Critically endangered.

- Victim to habitat loss and poachers (rhino horns are still used in traditional Asian medicine).

- Less than 80 estimated left in the wild in Indonesia.

What can we do?

We average Malaysians can do more than applaud heads of state and cheer rescue missions from the sidelines. Poachers won’t kill what they can’t sell, so it’s crucial to stop the purchase of products using exotic and, more importantly, endangered animal parts.

Also volunteering with or donating to organisations such as the Borneo Rhino Alliance, WWF-Malaysia, and Sumatra Rhino Rescue also make a dent in helping stave off the extinction of the Sumatran rhino population.

Filmmaker and National Geographic photographer Ami Vitale, who covered Sudan’s dramatic transport from a zoo in icy Czech Republic to the sun-drenched plains of Kenya, and the creature’s death nine years later, wrote: “My hope is that Sudan’s legacy serves as a catalyst to awaken humanity to this reality.”

“But if there is meaning in Sudan’s passing, it’s that all hope is not lost.

“This can be our wake-up call. In a world of more than 7 billion people, we must see ourselves as part of the landscape. Our fate is linked to the fate of animals.”

If Sudan’s death opened our eyes, what will Tam’s legacy be?

This piece was originally published on Between The Lines, a weekday newsletter that curates the most important news stories of the day and explains the context behind them. Subscribe for free here.