Optimise your mental wellness with VitaHealth CHARGE-UP™

Leaving office comforts to fill hungry stomachs

Leaving office comforts to fill hungry stomachs

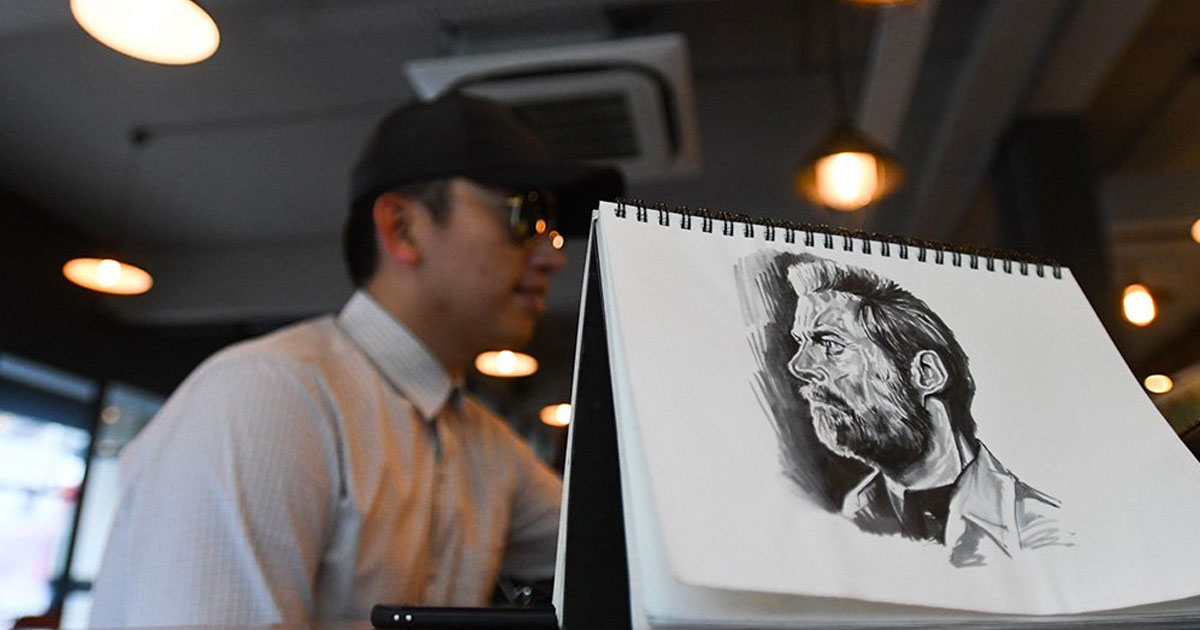

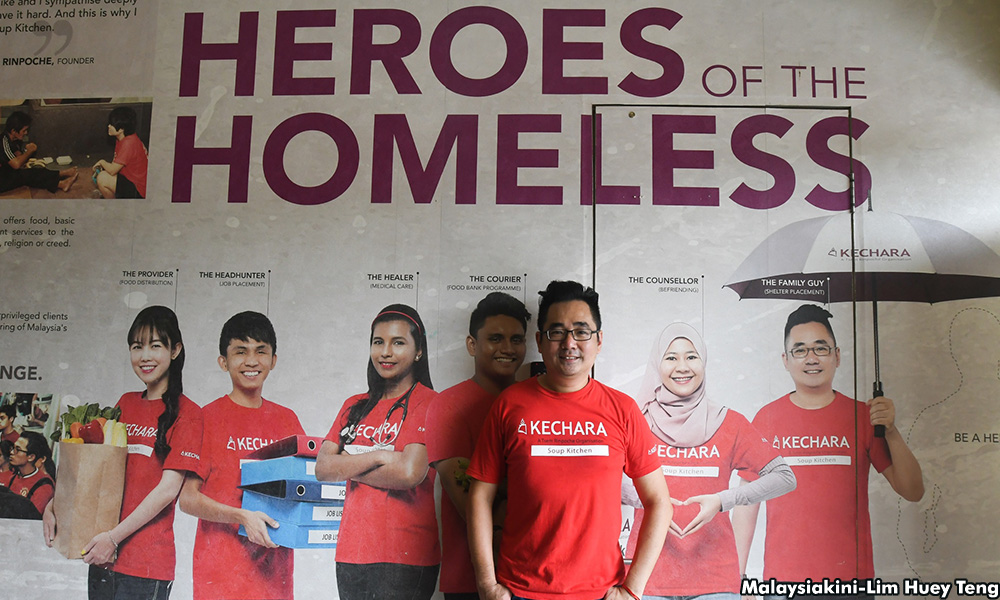

With great care, Justin Cheah assembles each nasi lemak packet, putting an extra fried egg in one, adding more rice in another, while bustling in and out of the kitchen.

“Some of our volunteers are not coming today, so I’m helping the team out,” explains Cheah, before excusing himself to meet with one of his clients, an aged woman looking for a job.

Cheah works with Kechara Soup Kitchen (KSK), a non-religious community action group that distributes food and provides basic necessities for the homeless and the urban poor.

The 41-year-old KSK project director left his banking job of 11 years to fully commit to the cause after joining one KSK initiative in 2006.

Based in Pudu, Kuala Lumpur, the group distributes some 250 packets of vegetarian food daily, save for Sundays, throughout the Klang Valley.

“You’ve caught me at the right time. We’re just about to serve lunch, and later we’re going out to distribute the rest of our food,” he remarked, pointing to a line of about 20 men and women eagerly waiting for their hot meal.

After making sure that everyone has received their lunch, Cheah tells Malaysiakini how he got involved with KSK, and why he has not looked back since:

I GOT INVOLVED IN 2006 AFTER BEING INSPIRED by the story of Kechara’s founder, Tsem Rinpoche. His story of being homeless for two weeks in America and having no food made me start to think about the homeless, something I had not bothered to do for the previous 30 years of my life.

Prior to volunteering at Kechara, the only contribution I would make towards the homeless would be pushing coins inside the odd donation box that came my way. But one Saturday in 2006 changed my views forever.

WITNESSING HOMELESSNESS FIRSTHAND OPENED MY EYES. I found out Kechara had a soup kitchen, and on Saturday evenings I would go with my friends for their weekly distribution events to help the team out.

The first Saturday, when I got off the van, I saw people with crutches sleeping on the cold, hard floor, some clearly starving. I also saw an old lady pushing a trolley with what seemed to be her belongings.

Of course, I had seen homeless people before, but at that point, I started to wonder why.

The team entrusted me with serving out the food. I had no idea what I was doing. While setting up, I noticed a group of people had already gathered around the van, waiting anxiously for food.

At the end, seeing those who I had served hungrily wolfing down their meals, I realised I wanted to do it again the following Saturday. And I came back every Saturday.

I LEFT MY 11 YEAR JOB TO FULLY COMMIT TO THE CAUSE. I left my banking job to pursue my own business. But even after leaving the corporate life, I started to wonder, what was life all about? Was I just meant to climb up the corporate ladder? And then what?

While giving out to the poor, I used to remember being really happy. And I didn’t have to go to the office too. Even happier!

But jokes aside, I felt the work I was doing at KSK was meaningful. The time spent in the office could very well be spent helping people instead. And why not?

My job as the KSK project director is to primarily make sure our premises are clean, and also to ensure everyone’s needs are taken care of.

This includes checking the quality of the food we get from sponsors to meeting with those who show up on our doorstep, asking for our help to find jobs.

Having been involved with KSK for the last ten years or so, I want to now work even harder for the benefit of those who depend on us. How are we able to provide solutions? How can we help get homeless off the streets?

“THEY CHOOSE TO BECOME HOMELESS, AND ARE ALL LAZY” are just some of the things I hear from people. Generally, those who do not understand the issue at hand tend to say things like this.

The stigma Malaysians attach towards the homeless is really bad. If we are going to reject an entire community of people simply because they are on the streets, how will this solve the problem?

Each individual and each one of their stories is multi-layered, explaining why they did what they did, and how they ended up where they are.

Homelessness is not a choice, and we cannot just sweep the issue under the carpet.

Through KSK’s work for the last ten years, we have developed a database of sorts, amounting to 6,800 profiles of homeless people in Kuala Lumpur.

These include those on the brink of homelessness, or who are already homeless. 80 percent of them are uneducated; some are dropouts; some had never received a secondary education. 18 percent have serious issues such as pneumonia and mental health concerns. Some 70 percent suffer from poor upbringing – no stable family, no home, et cetera.

The problem here is the homeless do not have a support system. They do not just need a free meal – they need a place to stay, and a job to get them off the streets. For that they need clothes, they need medicine, and that is what KSK is doing.

THEIR SMILING FACES KEEP ME GOING. Sometimes people ask me, “Why do you help these people? Most of them are ex-convicts, alcoholics, drug users”. While I agree with these general assumptions, this does not get to the root of the problem.

When you look at people whom you have helped wave at you in thanks, or simply smile when they bump into you, does it not warm your heart?

This is the sort of fulfillment I get on a daily basis. Not just praise from Facebook about the work I did, mind you, but to actually live my life meaningfully. There is nothing that beats this feeling.